Blueprint Labs Research Associate Russell Legate-Yang and Predoctoral Researcher Fatima Djalalova contributed to a new Blueprint working paper, “Putting School Surveys to the Test,” authored by Josh Angrist, Peter Hull, Legate-Yang, Parag Pathak, and Christopher Walters, which studies the links between school surveys, standardized test scores, and long-term student outcomes. In this spotlight, Amanda Schmidt connects with Russell and Fatima to discuss the study’s results, policy partnerships, and more.

Tell me about this study. What questions were your team hoping to answer, and what motivated this work?

School districts have traditionally relied on standardized test scores to measure school quality, but there’s been a significant shift toward incorporating non-academic measures in quality reports. The 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act requires states to include multiple measures of school quality in school accountability reports, highlighting the option to use non-academic factors. As part of this change, student surveys have emerged as one way to measure school climate and engagement. Currently, fourteen states either include or plan to include school climate survey data in their accountability statistics, and survey providers like Panorama Education serve 25% of U.S. K-12 students.

New York City Public Schools (NYCPS) represents a leading example of this trend. In 2014, NYCPS moved away from a test-score-heavy accountability system to one that emphasizes survey data, with the goal to provide a more complete picture of school performance. The focus on surveys reflects a growing recognition that school climate and student engagement are valuable. This shift toward survey measures raises important questions: How well do survey measures predict students’ longer-term success compared to test scores, and does combining survey and test score measures provide a more complete picture of school quality?

To answer these questions, we studied middle and high schools in New York City. NYCPS serves approximately 900,000 students across all grade levels, making it the largest school district in the United States. Besides being an early and influential adopter of school surveys, NYCPS’s school enrollment system also provides a useful setting to study school quality. Some students in NYC are exposed to random assignment to schools through school enrollment lotteries. This feature enables us to measure school causal effects: the magnitude of improvement in student performance on standardized tests, responses to survey questions, or college attendance when randomly assigned to one school versus another. This causal effects approach isolates school quality from differences in student background, demographics, or prior achievement. We measured each school’s causal effects on students’ short-term outcomes (test scores and survey responses) and longer-term outcomes (high school graduation and postsecondary attainment). We then examined two key relationships between school effects and different outcomes: how well test scores and survey measures each predict students’ longer-term outcomes, and whether combining both measures provides better predictions than using either alone.

You partnered with New York City Public Schools to conduct this study. How did your collaboration with NYCPS inform your work?

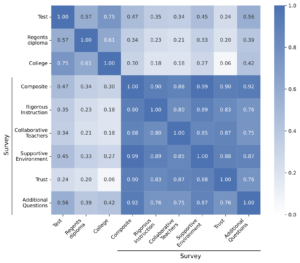

Our collaboration with NYCPS was instrumental to this research. Throughout the project, we maintained close communication with the NYCPS school performance division, which monitors school quality metrics and develops strategies to evaluate and enhance educational outcomes across the district. Our ongoing dialogue with the school performance division enhanced our understanding of the city’s school system, data structure, and measurement framework. NYCPS’s detailed feedback throughout the research process helped strengthen our analysis. For example, based on these conversations, we added a table that displays correlations between school achievement levels and various survey measures. This table reveals strong correlations within academic measures (test scores and longer-term achievement) and within survey measures, but weak correlations between academic measures and survey responses. This finding suggests surveys capture school quality dimensions beyond academics, which motivated our investigation into causal relationships.

Figure: Correlations between School Achievement Levels and Surveys

This research naturally evolved from our long-standing partnership with NYCPS. We had previously developed school ratings that NYCPS now publishes on their School Performance Dashboard. Since this dashboard presents both test and survey information to families, NYCPS and Blueprint Labs were interested in understanding whether and how these different measures predict students’ longer-term success.

What challenges did you face conducting this research? How did you address those challenges?

One challenge was understanding how to meaningfully compare test-based and survey-based school quality measures. We needed to establish an appropriate framework to understand what each measure captures, to evaluate their relative importance, and to identify which student outcomes would provide the most meaningful basis for comparison. Our results demonstrate that both test and survey-based quality measures can predict how schools affect high school graduation and college attainment. These outcomes are a major focus of education policy and are linked to later life outcomes like earnings. Surveys may have other roles in school accountability systems, though, since parents and students value aspects of schools like safety or positive climates regardless of effects on college-going odds.

Beyond comparing these measurement approaches, we sought to ensure the robustness of our findings across different student populations. Since our initial value-added models were developed for the overall student population, it was critical to examine potential variations across demographic groups. To address this concern, we re-estimated our models separately by race, gender, and free lunch status. The consistency of results across these subgroups reinforced the validity of our main findings.

What were the results from this study?

We found that both survey responses and test score measures provide meaningful signals about schools’ effectiveness, as measured by receipt of standard and advanced high school diplomas (advanced diplomas require additional courses and exams), college enrollment, and college persistence. Students who attend high schools that improve survey responses by one standard deviation (from median survey responses to the 84th percentile) are 11 percentage points more likely to earn a standard diploma and six percentage points more likely to enroll in college. The effects are more modest in middle school, with only a three percentage point increase in graduation with a standard diploma and no effect on college enrollment.

Students who attend high schools that improve test scores by one standard deviation (from median test scores to the 84th percentile) are nine percentage points more likely to graduate high school and 11 percentage points more likely to attend college. In middle schools, improved test score value added predicts a 17 percentage point increase in college, though only a two percentage point increase in high school graduation.

When examining both measures together, we discovered distinct patterns in their ability to predict longer-term outcomes. Test scores emerge as stronger predictors of advanced diploma attainment, college enrollment, and college persistence outcomes, while surveys show particular strength in predicting standard diploma receipt.

What comes next for this research? What are the policy implications of this work, and what direction might future research take?

Our findings have important implications for school quality measurement, particularly for districts that lack NYCPS’s comprehensive framework that provides multidimensional school quality metrics. While surveys better predict high school graduation and test scores better predict postsecondary attainment, neither metric predicts these longer-run outcomes perfectly. Causal estimates of school effects on longer-term outcomes are consistently the strongest predictors. For example, a causal estimate of a school’s impact on college enrollment is the most informative guide for families aiming to boost their child’s postsecondary outcomes.

Looking ahead, several key research directions emerge. First, NYCPS’s recent addition of graduation and college value-added metrics to its School Performance Dashboard creates an opportunity to study how new information affects family choice and student outcomes. This research will illuminate what parents value in schools and how information about different school performance metrics influences their choices. Second, we plan to study whether our findings hold across other districts with different survey instruments and quality measurement systems.

Interested in learning more? Read the working paper or the policy brief.