Josh Angrist is the Ford Professor of Economics at MIT, a co-founder and director of MIT’s Blueprint Labs, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Angrist’s innovative empirical strategies, recognized in the 2021 Nobel prize in Economics, harness the power of natural experiments to answer important economic questions. Examples include the use of draft lottery numbers to estimate the effects of Vietnam-era military service, the use of charter school admissions lotteries to estimate the effects of charter school attendance, and the use of season of birth to capture the causal effects of education on wages. These are just three of the many creative applications pioneered in Angrist’s scholarship. Beyond applications, Angrist and co-laureate Guido Imbens developed a novel theoretical framework for the interpretation of the causal effects uncovered by natural-experiment research designs. This framework increases the scope and relevance of natural experiments.

Click on the buttons below to learn more about Angrist’s empirical research on important economic questions.

Economists have long debated the importance of class size in learning. Paradoxically, children in larger classes appear to learn more. But perhaps this reflects the fact that classes are larger in high-income areas.

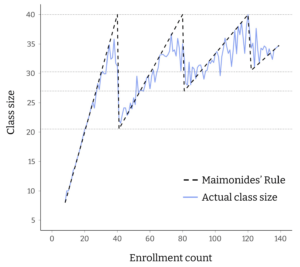

Josh Angrist and economist Victor Lavy pioneered the Maimonides’ Rule research design, an innovative mix of instrumental variables and regression discontinuity methods, to understand the effect of class size on student achievement.

In Israel, class size is capped at 40 students. This simple rule, Maimonides’ Rule, generates sharp drops in class size as a function of enrollment. Figure 1 shows what this means in practice.

Figure 1. Class size in 1991 by initial enrollment count

Angrist and Lavy’s approach uses this up and down pattern to capture class size effects as in a randomized trial. Using the rule as an instrument for class size and focusing on the schools with enrollment close to rule cutoffs, they find that reducing class size increased test scores for Israeli elementary school students in 1991.

To learn more, see Angrist and Lavy (1999) and Angrist et al. (2019).

Over the past twenty years, charter schools have become increasingly prevalent in the US. From 2000 to 2017, the share of total public school students enrolled in a charter school increased from two to seven percent. Economists and policymakers are eager to understand the causal impact of charter schools on student outcomes.

To compare schools, directly looking at test scores can be misleading. Differences in test scores can often be explained by already-present differences in ability, rather than a school’s quality of education.

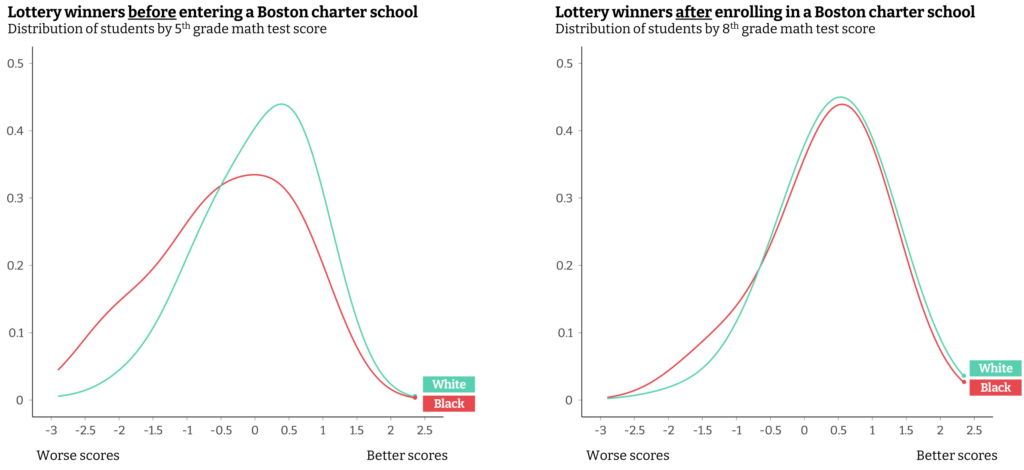

For this reason, Angrist and his colleagues employ a lottery-based research design in their charter school studies. Charter schools often use lotteries when they receive more applications than their number of seats. Comparing lottery winners and losers over time reveals differences in outcomes driven only by charter school attendance. Angrist has used this lottery methodology to study charter schools across the country, including in Boston, Chicago, Denver, Lynn, and New Orleans.

In the first evaluation of charter schools in Boston, Angrist and his colleagues generate lottery-based estimates of charter effectiveness. Charter schools lead to large and significant test score gains for students. The vast majority of Boston charter students are low-income, students of color. They enter charters with baseline test scores well below the state average. Boston charters greatly increase test scores for this historically underserved student population. In fact, in charter schools, the black-white test score gap is eliminated in a few years of attendance (as highlighted in this New York Times article). Figure 2 shows this shrinking racial test score gap.

Figure 2. Effect of enrolling in a Boston charter school on black-white achievement gap

In a follow-up study in Massachusetts, Angrist and colleagues find that the positive effects of charters are largely driven by urban charter schools adhering to the “high expectations, high support” pedagogical style (often previously called “No Excuses” pedagogy). These schools focus on strict discipline, frequent teacher feedback, increased time in school, data-driven instruction, and high-intensity tutoring. In some sites, such as Denver, charter school effectiveness is driven almost entirely by charter schools run by a charter management organization (CMO).

To learn more about the research on charter schools in:

In recent years, parents and policymakers have fiercely debated exam schools. These schools are highly selective public schools with admissions based on academic performance. Seats are heavily rationed, and some believe the student bodies should be diversified. Given their popularity and controversies, it is critical for policymakers to understand if exam schools are effective and who they benefit the most.

Comparing test scores of students at exam schools with those who attend other schools can lead to misleading findings. Students attending exam schools may enter with higher grades, have higher ambition, or differ in other ways. Josh Angrist, Atila Abdulkadiroğlu, and Parag Pathak measure the effects of exam schools in Boston and New York using regression discontinuity design. In other words, they compare students just above and just below the test score admissions cutoff. As a result, any differences in outcomes can be attributed to the exam school.

Surprisingly, exam schools in Boston and New York have no effect on student outcomes, leading to what Angrist and his colleagues dub the “Elite Illusion.” In Chicago, the findings are even more surprising. Attendance at exam schools has a negative effect on students’ math scores. Exam schools divert students away from attending the very effective Noble Network charter schools. As a result, students around the admissions cutoff who attend exam schools perform worse than their counterparts who attend another school (oftentimes, a Noble school).

To learn more, see Abdulkadiroğlu et al. (2014), Abdulkadiroğlu et al. (2017), and Angrist et al. (2021).

Many states, school districts, and information-sharing platforms report measures of school performance. Often called “school ratings,” they are widely consulted by parents and educators alike. Families looking for a new home are likely to see ratings posted alongside listings, while low-rated schools may be closed or placed under state supervision.

For economists, a school’s “quality” is defined as its causal impact on student achievement. High quality schools excel at boosting achievement for students of a given background and preparation level. However, some ratings have selection bias, meaning they are influenced primarily by student background and preparation rather than by causal school effects. Josh Angrist, Peter Hull, Parag Pathak, and Christopher Walters have analyzed school ratings and produced new, more accurate measures of quality.

There are two primary types of ratings. Levels ratings reflect average test scores, while progress ratings look at growth across grades (commonly referred to as student growth percentiles). Progress ratings better predict school quality than levels ratings because they have less selection bias.

Angrist and co-authors examine whether they can improve upon conventional methods in New York City (NYC) and Denver. Using data from centralized assignment systems, they effectively remove selection bias to provide a highly accurate measure of school quality.

They also analyze the frequent correlation between a school’s rating and the racial make-up of its student body. Higher-rated schools tend to have a greater percentage of white students. More specifically, levels ratings are highly correlated with race, while progress ratings are less correlated with race.

For middle schools in NYC and Denver, the racial make-up of a school’s student body is largely unrelated to school quality. Thus, selection bias drives the correlation between widely used ratings and student racial composition. Many schools rate higher simply because they serve students who tend to have higher test scores regardless of school quality (e.g., higher-income students). In light of this finding, Angrist and co-authors develop a novel “race-balanced progress” rating. This measure is uncorrelated with race but just as predictive of school quality as conventional progress ratings.

To learn more, see Angrist et. al (2021) and Angrist et. al (2022).

Governments and foundations spend enormous sums on college aid every year. Given the finite amount of funding, economists and policymakers are eager to know how and for whom scholarships generate the most positive impacts.

In 2011, Josh Angrist, David Autor, and Amanda Pallais partnered with the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation (STBF), one of the largest private funders of college scholarships in the country. STBF offers scholarships to Nebraska high school graduates, covering the full cost of tuition and fees.

In partnership with STBF, Angrist, Autor, and Pallais implemented a partially randomized study of financial aid. After students apply, they are scored on a variety of factors. The highest applicants receive aid, while the lowest do not. Angrist and his colleagues focus on the middle group – all are equally qualified for an award. In the randomized study, STBF randomly awarded scholarships to half of this group. As a result, any differences in outcomes between the winners and losers reflect the causal effect of the STBF scholarship.

Angrist, Autor, and Pallais find that STBF awards lead to large gains in college enrollment, college persistence, and degree completion. In addition, they find a “merit aid paradox.” Award effects are modest or absent in groups with strong high-school achievement and high ACT scores, groups usually deemed worthy of support. Meanwhile, award effects are largest for historically disadvantaged students and those typically expected to be less likely to graduate. The scholarship program is the most cost effective for the historically disadvantaged student subgroups. Together, these findings suggest that increased targeting of financial aid awards is likely to enhance aid impact.

To learn more, see Angrist et. al (2021) and Angrist et. al (2017).

Economists have long sought to measure the economic returns to schooling. Students with more years of schooling have higher earnings. However, this correlation may be an artifact of selection bias.

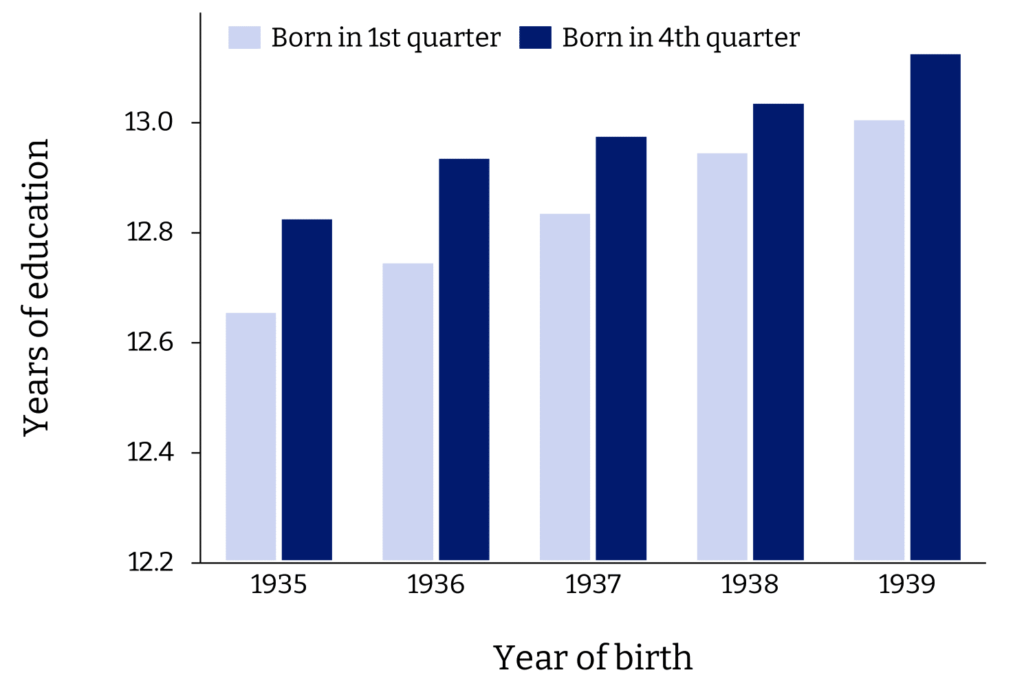

Josh Angrist and Alan Krueger pioneered an instrumental variables strategy to measure the earnings return of an additional year of schooling. Compulsory schooling laws require that students attend school until their sixteenth or seventeenth birthday, after which they can drop out. School start age policies require that children born in the same calendar year all start school on the same date. Taken together, some students can drop out of school one year earlier than others simply because of the place of their birthday in the calendar year. For example, a student born in February will turn sixteen one school year earlier than a student born in October of the same calendar year.

The place of a birthday in the calendar year is due to chance. Angrist and Krueger use a student’s quarter-of-birth as an instrument for schooling. Figure 3 shows a strong first stage – students born later in the calendar year receive more schooling.

Using data from the 1970 and 1980 Census, this approach reveals that an additional year of education leads to ~8 percent higher adult earnings.

To learn more, see Angrist and Krueger (1991).

Figure 3. Years of education by quarter of birth

A causal link between child-bearing and labor-force participation can explain post-World War II increases in female labor supply. Many observational studies document a negative correlation between fertility and labor-force participation. However, child-bearing and the decision to work are likely jointly determined.

Josh Angrist and economist Bill Evans introduce a creative instrumental variables strategy to measure the effect of having a child on employment outcomes. They instrument family size with the sex composition of parents’ first two children. Their key insight is that parents prefer that their children are not all the same sex. For example, parents whose first two children are both boys are more likely to have a third child (in the hopes of having a girl) than parents whose first two children were a boy and a girl. The validity of the instrument turns on the gender of parents’ first two children being due to random chance.

Using data from the 1980 Census, this approach reveals that having more than two children decreases a mother’s likelihood of working by ~13 percentage points, weeks worked per year by ~6 weeks, and annual income by ~$2,200 (in 1995 dollars). However, there is no detectable effect of an additional child on the employment outcomes of fathers.

To learn more, see Angrist and Evans (1998) and Angrist and Fernandez-Val (2013).

Many federal benefits programs are designed to compensate veterans for their military service. An implicit question is whether veterans are economically worse-off due to their service. Many observational studies show that veterans have lower post-war earnings than civilians. But perhaps this is because veterans have worse job prospects than civilians.

Josh Angrist uses draft lotteries to uncover unbiased effects of military service on post-war earnings. In the 1970s, the US government held draft lotteries to select young men to serve in the Vietnam War. Angrist instruments military service with the draft lottery number. He finds that for white veterans, serving in the military decreased early-career post-war earnings by ~15%.

In a follow-up study, Angrist and economist Stacey Chen use the same lottery-based research design to study the impact of military service on late-career earnings and find no effect. They argue that this non-impact combines two counteracting forces: (i) military service increasing schooling through the G.I. bill which boosts earnings and (ii) military service lowering work experience which decreases earnings.

To learn more, see Angrist (1990) and Angrist and Chen (2011).

Angrist is currently investigating the long-term impacts of attending a charter school by linking charter lottery records with data on employment, earnings, and criminal justice system engagement. In another project, Angrist is merging randomized financial aid offer data with students’ post-secondary outcomes to study the long-run effects of financial aid.

On the methodology side, Angrist and co-authors have recently made substantial progress using centralized student assignment systems in schools to perform causal inference. They are now investigating new questions on how to best develop these tools. If you are interested in collaborating with Angrist or learning more, please reach out to contact@mitblueprintlabs.org.

Subscribe for Updates